Claspology

by Reinhold Ludwig (Schmuckinstitut Ulm)

When Germans hear the term “Schloss” (which means “castle” or “palace” as well as “lock” and “clasp”), they don’t usually think of a jewellery clasp but rather of the device that locks doors, gates, or bicycles.

For those with an interest in aristocracy, the word brings to mind magnificent lordly mansions and other opulent buildings like the castles and palaces of Versailles, Schonbrunn and Neuschwanstein. These are exceptional historic monuments, built as residences for the European aristocracy in the Renaissance, starting in about the 16th century. By the 19th century, with the rise of modern forms of government, the era of these palaces was over, even though some are still inhabited by royal families and even used by politicians and others for public events. They are clearly remnants of a bygone era, and have a museum-like aura, but we value them nonetheless. In fact, we’re still building them (including in Berlin), even if we can’t afford to. People need such palaces to keep alive their memories, which help them heal the wounds of the past and to establish a national identity.

The palaces and castles of the Renaissance and Baroque periods were based on ancient theories of form and proportion. Harmoniously structured, built with precious materials, equipped with rich furnishings and surrounded by wonderful gardens, such buildings can rightly be called the largest pieces of architectural jewellery ever made. This definitely cannot be said about a door lock, even if it has some decorative elements in addition to its dominant feature, functionality. The play on the different meanings of the German word “Schloss” is derived from its origin, “schliessen”, which means “to close”, “to lock”, or “to fasten”. But whereas the door lock is used to lock something or someone in or out, the jewellery clasp serves only noble purposes. It is not used to lock a precious piece of jewellery away and hide it, but instead to show it. It is true that the jewellery clasp also prevents us from losing a piece of jewellery, but it doesn’t deny our access to it.

Simply “Fibulous”

The jewellery clasp dates back to antiquity. It began when people started to forge metals in order to manufacture weapons, tools and jewellery. The clasps’ oldest form, two wire ends bent into hooks, was easy for the people in the Bronze and Iron Ages to make by hand. An example of such a primitive clasp is the torque in the Crafts Museum of the city of Cologne, crafted around 1000 years B.C. This collar necklace, wrought from silver, has a thickened section on the front as a decorative element. The hook catch on the back serves only to join the two ends.

It took thousands of years for the clasp to be allowed to move to the front of a necklace and be worn as a decorative element. Until then, it led a charming but rather hidden existence in the back of its wearer’s neck, often covered by soft curls or thick waves of hair, serving only a functional purpose, namely holding together the ends of a necklace. It was forbidden to be in the limelight with a magic aura of its own. However, the clasp began its evolution toward jewellery status early in history, thanks to an ingenious instrument that combined decoration and function for the first time. Probably because sewing was so laborious back then, the ancient peoples in Eurasia invented the garment pin, called a fibula. This word, from Latin, is synonymous with “fibigula”, whose basic form, “figere”, simply means “to fasten” or “to pin”. A fibula is a metal pin consisting of a needle, a bow and a spring, used to hold garments together and usually serving also as a piece of jewellery. In the field of archaeology, it still has an important function today. Because it can be related to specific traditional or national costumes, and due to its great variety of forms, the fibula is one of the most important tools for studying antiquity. The different types of fibulas help to distinguish historical eras and regional ethnic groups. They were given specific names, based on their shape (e.g. eagle fibula, eye-shaped or crossbow fibula), their dispersal (e.g. Luneburg fibula) or the place where they were found. The oldest fibula is thought to be the two-part golden plate fibula from a prince’s tomb at Alaca Huyuk in Anatolia (3rd millennium B.C.). In the 14th and 13th century B.C., both one- and two-part fibulas were used. The one-part fibula (violin bow fibula and bow-shaped fibula), which was the model for our safety pin, originated in southern Europe. In the later Iron Age, from the 5th to the 1st century B.C., eye-catching fibulas shaped like various animals and masks held furs and robes together. In the time of the Roman Empire, the eye-shaped fibula became important. It also served as a model for the fibula in the Middle Ages, when this type of pin enjoyed its last wave of popularity.

The goldsmiths of the Romanesque period embellished their fibulas with gemstones and niello. The “accommodating strangers” scene in the stained glass of the northern rose window of the Freiburg Cathedral from around 1250 shows a particularly good example of a golden fibula adorning a rich lady wearing a yellow cape. In the book on falconry written by Emperor Frederick II, “De arte venandi cum avibus” (About the Art of Hunting with Birds) from the 13th century, this Hohenstaufen emperor is seated on his throne wearing a blue robe held together by a round fibula.

Close Relatives

The closest relative of the fibula is the brooch, worn for hundreds of years and, of course, still popular today. In Meyer’s Encyclopaedia, the following can be read about it: “Brooch, French for pin used in female fashion, made of precious metal, often adorned with gem-stones. The brooch can be worn exclusively as a piece of jewellery but can also serve to hold things together, e.g. a collar, and thus assume the function of a fibula. Early forms of brooches are found in the Renaissance period.”

The encyclopaedia describes the heyday of the brooch in the 19th century and mentions that it experienced a subsequent bloom in the decorative forms of the Art Nouveau period around 1900. About the clasp, the encyclopaedia states the following: “Term for a non-specific fastening device in garments; outstanding examples are the elaborately crafted clasps in Medieval Church vestments; also called fibula or brooch.” Thus, the close relationship between the fibula, the brooch and the clasp has been confirmed. The creative efforts of the goldsmiths and artists of the past to craft eye-catchers are documented by other jewellery objects similar to the clasp and the brooch, which completely do without a clasp function. Up to the 16th century, garments and hats were often adorned with agraffes sewn to them. As an eye-catcher, the agraffe is similar in form to the brooch and the disk fibula. However, it is firmly attached to the garment or hat. Whereas the agraffe is shaped as a decorated disk, the musk apple challenged the European goldsmiths in the late 15th century elaborately to craft perfectly sculptural spheres. Musk apples became fashionable in the Renaissance period. However, they were meant not only to adorn but also to carry something that made them even more precious: highly fragrant musk.

Form Includes Function

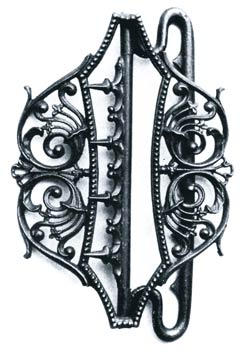

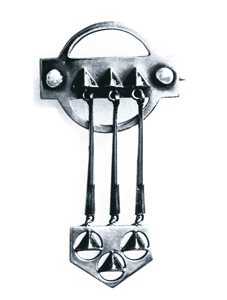

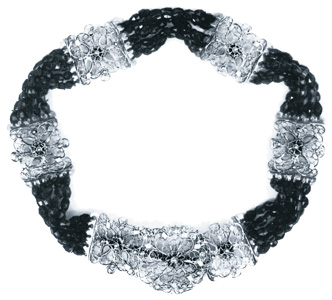

In the development of the clasp into a fully realized jewellery object, the belt buckle plays a major role. Due to its prominent position on a person’s belly, it couldn’t help but become a fashionable object. And because we can handle things much more easily in front of us than behind us, there has never been any doubt as to where to place the belt buckle. In the Biedermeier period of the 19th century, belt buckles were downright fashionable. They were often made of cast iron, such as the buckle designed by Siméon Pierre Devaranne from Berlin, which can be seen in the collection of the Crafts Museum of the city of Cologne. This collection also includes a striking belt buckle consisting of two lion head medallions hooked into each other, designed by the famous French Art Nouveau goldsmith René Lalique and crafted around 1900. The lion head motif is atypical of Lalique, and was probably suggested by his client, who may have been inspired by a lion head doorknocker. For fastening the two buckle pieces to a belt, the backs of both are equipped with three eyes made of a flat wire. The Art Nouveau and Art Deco periods produced countless new jewellery forms and genres. But it was not until the second part of the 20th century that the technically perfect, completely integrated jewellery clasp for necklaces had its breakthrough, thanks to Jorg Heinz from Pforzheim, Germany, who invented and developed it. It is true there were front-closing necklaces as early as the 19th century. One example is the “Halsbatti mit Roslistucken” from Switzerland. This choker, fairly typical of Swiss costume of the time, has a decorative section – designed to be much more prominent than the rest of the necklace – that covers the clasp in front so that it doesn’t detract from the choker’s harmonious design.

Jörg Heinz

Jorg Heinz’s clasps, in contrast, comprise a wide variety of imaginatively designed spheres or other decorative elements in which the precisely engineered clasp mechanism is completely integrated and thus invisible.

Traditional box-shaped clasps, even those designed as decorative objects to be worn in the front, never achieve this. Heinz’s clasps therefore mark the final chapter in a history that began in the Bronze Age and continued